JIG STRATEGIES FOR ICY STEEL AND BROWNS

TIMELY TOPICS

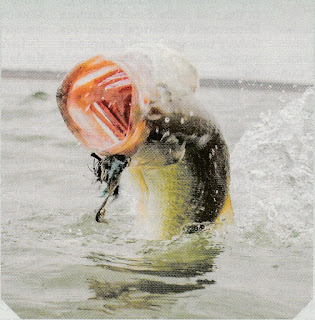

From far across the icescape, wind picks up fetch. Tiny spears of wind-driven ice

pepper our suits. Steelhead and trout might be out there, as far as the eye can see,

out where ice or water meets sky. Or they might be underfoot.

Out there

somewhere, a “wave” comes through and everyone1 the tip of a dangerously bent

ice rod in the the hole so line won’t bury in the ice. Spools on the,. blur

like electrons racing around a nucleus. Some fish hit spoons, some hit bait.

“My grandma would have landed that fish by

now,” somebody laughs, a precocious “skipper” dancing on the ice by his feet.

“Your grandma was a linebacker for the Lions,” another says, pumping to gain

line on a bigger fish.

It takes a

while. Plenty of give-and-take. Finally a crimson-tinged silver bullet slides

out of the hole. How far did it travel today, to end up here at your feet?

Where has it been? Is it going up the river, up the shoreline, or back out to

the expanse?

Timing the

Bite

Ice fishing for steelhead and brown trout involves more than just two populations of fish. One portion of the steelhead population intends to run up rivers and spawn, while another portion remains in the big lake. The latter group is composed of two-, three-, and some four-year olds that won’t spawn during the current cycle. Those fish are wandering, feeding machines. The former group, made up of fish intending to spawn, can be less likely to react to aggressive presentations.

Ice fishing for steelhead and brown trout involves more than just two populations of fish. One portion of the steelhead population intends to run up rivers and spawn, while another portion remains in the big lake. The latter group is composed of two-, three-, and some four-year olds that won’t spawn during the current cycle. Those fish are wandering, feeding machines. The former group, made up of fish intending to spawn, can be less likely to react to aggressive presentations.

Many rivers have both fall and spring runs, dividing the population into groups that behave differently. Spring-run fish are more likely to roam farther up and down the shorelines, and farther out to sea. Some stay miles offshore all winter, rarely offering ice fishermen any windows of opportunity. Fall-run fish may roam around when conditions aren’t right for running the river, but probably stay closer to “home.”

When conditions are ideal for running rivers in October and November, there are far fewer fall-run steelhead under the ice around piers and harbors of the Great Lakes. Most are upriver, meaning ice fishing on slow, put-and-take rivers in farm country will be great—not to mention open-water fishing in all those hill-country rivers that never freeze. If autumn brings little rain and rive rs remain too low and clear, most fall-run steelhead stay in the lake, and ice-fishing opportunities can be awesome. Fall water levels are good big-fish indicators for ice fishing succ ess months later.

Then you have the extremes. Some Lake Superior streams with only fall- run strains never hold fish in fall or winter because they freeze solid or never have enough water in fall for fish to keep their backs wet. (Yet amazingly, many of those streams have great populations of naturally- reproducing steelhead.) After more than 100 years of following that patt ern, those fish know the drill. They continue roaming open water well away from the rivermouths until late winter, when days get longer and thaws begin to fill those streams up.

Brown trout can be a mixed up lot. Many strains have been planted, and each strain tends to behave diff erently. Specimens of the amazing Seeforellen strain (which attains the greatest size) behave like steelhead, running rivers in fall and often stayi ng upstream all winter. Other strains rarely seem to run rivers. They spawn on gravel beaches and spread out all winter, not concentrati ng around rivermouths until a run of bait fish draws them in.

Plugging on Ice

Then there’s Ohio. Steelhead cruise the shorelines in waves everyw here around the Great Lakes. Most places a wave might include 10 to 50 steelhead. The harbors of western Lake Erie entertain something bett er described as a tsunami of 100 or more big ‘bows. The steelhead fishe ry is on fire in Lake Erie. “Steelhead definitely come through in waves,” says Craig Lewis, owner of Erie Outfitters just outside Cleveland. “They rush into the rivers looking for baitfish and push right back out. Some fall run-fish can be found holding in a big hole way upstream, and we’ve been able to ice-fish those holes on some rivers the past two years.”

Then there’s Ohio. Steelhead cruise the shorelines in waves everyw here around the Great Lakes. Most places a wave might include 10 to 50 steelhead. The harbors of western Lake Erie entertain something bett er described as a tsunami of 100 or more big ‘bows. The steelhead fishe ry is on fire in Lake Erie. “Steelhead definitely come through in waves,” says Craig Lewis, owner of Erie Outfitters just outside Cleveland. “They rush into the rivers looking for baitfish and push right back out. Some fall run-fish can be found holding in a big hole way upstream, and we’ve been able to ice-fish those holes on some rivers the past two years.”

The most popular method is jigg ing vertically with marabou jigs. “Spawn bags are not as popular here as jigs tipped with minnows, wax- worms, or maggots,” he says. “Up in Michigan, waxworms are king. Here it’s maggots. We have guides at Erie Outfitters that ice-fish for steelhead. Their primary method involves marabou or bunny-hair jigs tipped with livebait.”

But when conditions arise that generally initiate runs of steelhead (thaws, warming trends, rises in barometric pressure), Lewis pushes a plug into the hole at the end of a long ice rod and lets the current sweep it downstream. “In cold wint ers with dense ice cover and snow, we use Luhr Jensen Kwikfish and Yakima Flatfish,” he says. “Let out 10 feet of line, wait a minute, let it wander and wobble around, then let out three more feet of line, wait a minute, and repeat. We place holes strategically across the head of a pool to cover it all and duplicate what a drift boat would do with plugs in open water. Sizes are the K7 Kwikfish and F-7 Flatfish in black with a fluorescent head, all white, or fluorescent pink. We use 10-pound mono with 8- to 10-pound fluoro leaders.”

Strikes with plugs can be massive or just a cessation of action. When the wobble of the plug stops, set the hook. Steelhead and browns can surge forw ard and push slack into the line, or just clamp down on the invading lure, stopping the wobble. Sometimes the lure finds a current void. Sometimes it’s a leaf. Sometimes it’s a living dynamo. In any case, ripping the lure forward occasionally can’t hurt when trout are active.

“We downsize to fish jigs vertic ally,” Lewis says, “using 6-pound mono with 4- or 5-pound fluoro leaders under a small float on medium- light ice rods. Inmost conditions, we merely pick the float up and set it down with a marabou or bunny jig. The river gives it plenty of action. No need to overdo it. I use VooDoo Cust om Jigs in 1/80-, 1/64-, or 1/32-ounce sizes, depending on where we are, how clear the water is, and how fast the current. Upriver in small water we use white or black 1/80-ounce marabou jigs most of the time with a float, picking it up occasionally and dropping it back down. We’re allowed two lines each and six tipups, but rod-and-reel in hand is king around here. It’s not like you catch a fish and wait another hour. You may hook 15 in an hour and not have another bite for three hours. When a wave comes through, nobody wants to be chasing flags.”

When a tsunami

hits, the choice can be made for numbers or specimens. “Larger fish come off

structure or cover, like a rock bar or a bridge abutment,” Lewis says. “Maybe

those older fish need to rest more or tend to be smarter, but they orient to

current breaks like bridge pilings where you don’t pull waves of fish—just one

or two big ones. A big one can be 15 pounds or more.”

More Vertical Tactics

Outdoor writer and steelhead enthusiast Brian Kelly loves to ice- fish the harbors and rivermouths along the Eastern Basin of Lake Erie. “Usually first ice is excellent,” Kelly says. “If you have enough ice to stand on, you’ll find fish. Last year was cold early, and we were catching steelhead on ice the first week of December. The bite lasts through February or until the ice is no longer safe.”

Most Lake Erie

steelhead are fall- run fish. “The steelhead that haven’t matured yet are

cruising around looking for food,” he adds. “They enter harbors where smelt,

emerald shiners, and shad gather. Smelt show up later, usually January and

Februa ry, and we see a sudden bump in action again.

“Browns don’t run the creeks like they do in Lake Michigan. They seem to spawn on shoreline areas. Fishing stays consistent because the three- year-old steelhead roam the shorel ines, feeding heavily. Those fish come and go, depending on where the food is. Cameras and sonar tell that story quickly. The East Erie mix is about 75 percent steelhead and 25 percent browns. On Lake Huron we catch more browns. It’s 50-50 there.”

Kelly uses a variety of lures to jig in harbor areas. “Some years the big trout are more on live stuff,” he says. “Some years they really like lipless rattlebaits like the Rapala Rippin’ Rap or Strike King Red Eye Shad. Steelhead and browns clobb er those when you lift them just fast enough to make them begin to wobble and let them fall on a tight line. Acme Kastmasters and Little Cleos are classics. When the shad are running, they like a wider prof ile on the spoon, like the Cleo, PK Predator, or the new Williams Ridge Back. Doesn’t matter most years, but some years we can’t catch them jigg ing unless we put some meat on the spoon. We use a whole emerald shiner. You never need a stinger hook, they eat the whole thing.”

Rods and reels are standard. “We use Clam ice rods with 4- to 6-pound Seaguar AbrazX Fluorocarbon,” Kelly says. “Trout are not as line shy as they are on Lake Michigan so rod length isn’t critical. With long rods it’s hard to get them up the hole. The best ones are light walleye rods. If it’s too stiff, the action on the lure is too abrupt and hooks rip out. Steelhead hook themselves.”

Kelly fishes around harbor mouths about 10 to 15 feet deep. “Few of these East Erie harbors are deeper than 20 feet,” he says. “Steelhead school up, coming through in waves. Try to find an eddy off the main current in the harbor. For one thing, it’s safer than the current areas. Steelhead mill around in that slack water. Most of the time they use the top third of the water column. Use a portable shelter or cover your head over the hole with a piece of canvas and you can see them. We fish three feet under the hole a lot, watching the spoon. Out of nowhere there’s a flash and the rod’s doubled up.”

Hedging Bets

Some guides, like Chris Beeksma of Get Bit Guide Service on Lake Superior, depend entirely on spawn bags under Slamco Slammers or Automatic Fishermans—rod holders that maintain tension on the rod and line until a steelhead touches the bait. Then the rod snaps up and the hook is automatically set. “We fish in 3 to 6 feet of water outside wide rivermouths most of the time,” Beeksma says. “It works better to stay away from the hole unless you can sit perfectly still and be quiet for hours on end. We use jigs somet imes, too, to keep spawn bags tied with brown or steelhead eggs down in the current flowing out of the river. When current is slight, we use #8 or #6 Owner Mosquito Hooks. No need for sinkers on the line in those depths in either case.”

Beeksma and I use 1/64- to 1/32 TC Tackle Jigs colored with nail polish or powder paint in unique or unusual colors. We paint them in glow colors for warming-trend days when chocolate water rolls out of the rivers under our feet. Running to grab a thrashi ng rod before a steelhead yanks the entire operation down the hole is part of the fun.

Last winter lice-fished some of the slow, farm-country streams of eastern Wisconsin with Kerry Pauls on, inventor and owner of Automatic Fisherman, LLC. When I arrived, he and “Big” Mike Neta had six Autom atic Fishermans deployed over strat egic spots on a bend pool, several miles upstream of Lake Michigan.

Winter was wearing on. For steel- head holding upstream, the spawn was approaching. Feeding was no longer the priority. “Best to hedge your bets,” Paulson told me. “We catch more fish on spawn than lures in late winter because they aren’t aggressively eating. Spawn, on the other hand, excites them because it has to do with their main priority this time of year.”

We caught brown trout and some small precocious steethead with spoons, but none on rattlebaits. All the bigger fish—came on spawn bags presented on bare hooks or jigs under Automatic Fishermans,

Consider the season and the nature of the fish you’re likely to encounter out there. Upriver fish may be focused on things other than eati ng. Smaller, baited jigs and hooks tend to excel up there. But out where the wind peppers your jacket with daggers of ice, anything goes. •