Fishing Authority: If you want to catch bass, go where there are a lot of bass. If you want to catch

big bass, go where there are lots of big bass. Pretty obvious, but if you wait

for fishing reports, you might be too late. Here I make predictions of lakes

likely to produce memories in the near future.

When they were

newly impounded, southeastern reservoirs produced outstanding bass fishing, the

result of an upsurge of nutrients, good habitat, and expanding bass and forage

fish populations. Unfortunately, the boom was often followed by a bust. Fishery

management of southeastern rese rvoirs has come a long way in a relatively

short time, and bass have been a primary focus. Innov ative harvest

regulations, habitat management, and, in some cases, Florida bass stocking, has

resulted in bass fishing as good or better than in the “good ol’ days.”

Anglers have had

a role, too, actually, two roles. There’s no doubt that the widespread adoption

of volu ntary release has sustained the abundance of bass and, in many

fisheries, also improved size structure (the proportion of large bass). But

anglers also let mana gers know that quality was as or more important than

quantity in most waters. Bragging rights shifted from catching a 10-bass limit

to the combined weight of the best five.

Despite the experience, skills, and knowledge of today’s fishery managers, largemouth bass fishing in southeastern reservoirs still fluctuates. In some reserv oirs, climate and water availability strongly affect fish populations. In other areas, pressure from non-anglers affects habitat quality, like aquatic vegetation control or water level fluctuation, in multi-use reservoirs. Some conditions can’t be changed, but managers have learned how to manipulate bass populations to provide the kind of experiences anglers seek.

Fishery managers

are always proud to share success stories. But because so many factors affect

fisheries, it took a little arm twisting on my part to get them to make

predictions. Ultimately, I’ve assembled the stories behind some of the lakes

where bass fishing is “cycling up” in the next few years.

Falcon Reservoir, Texas

Down in Zapata in far South Texas where everyt hing sticks, stings, or bites is Falcon Reservoir, an 83,654-acre (at full pool) impoundment of the Rio Grande. “Falcon is all about water,” says Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologist Randy Myers, “but repeat stocking of Florida bass fingerlings also contribu tes to the large size structure.”

Strong largemouth bass year-classes were prod uced in 2004 and 2005 following substantial waterl evel increases. These fish fueled the boom from 2008 to 2011 that put Falcon in the record books for bass tournaments and attracted anglers from across the land. When the water fell, fishing faltered. Winning tournament weights (5-fish limit) dropped from 40-plus pounds in 2010 and 2011 to 24 to 26 pounds in 2015.

“Right now, increases in water level suggest a repeat of the strong year-classes that produced the phenome nal fishing in 2010 and 2011,” Myers says. “The low water in 2011 to 2013 allowed for a jungle-like growth or huisache, mesquite, acacia, and salt cedar on the exposed reservoir bottom.” Flooding of this vegetation provided the cover needed for high survival of young bass spawned or stocked in 2014 and 2015. Myers pred icts the next boom should start in 2017.

How good can fishing be at Falcon? Myers reported that creel surveys conducted during the 2011 boom estim ated 20,000 4- to 7-pound largemouths caught from January to June.

Best times to go: March to June for numbers and size.

"BASS FISHING

AS GOOD OR BETTER THAN IN THE ‘GOOD OL DAYS"

Lake Taiquin,

Florida

This 8,800-acre, 88-year-old impoundment near Tallahassee peaked a couple years ago, a result of stocking one-half million advanced fingerling (3- to 4-inch) Florida bass in 2000 through 2003, according to Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) fishery biologist Andy Strickland. Those fish started showing up as 8-plus pound bass in 2006. Winn ing tournament weights consistently have exceeded 25 pounds in recent years.

This 8,800-acre, 88-year-old impoundment near Tallahassee peaked a couple years ago, a result of stocking one-half million advanced fingerling (3- to 4-inch) Florida bass in 2000 through 2003, according to Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) fishery biologist Andy Strickland. Those fish started showing up as 8-plus pound bass in 2006. Winn ing tournament weights consistently have exceeded 25 pounds in recent years.

Talquin has been

managed with a 5-bass, :18-inch minimum length limit (one bass over 22 inches

allowed), with exemptions granted to certified catch-and-release tournaments.

FWC’s Aquatic Habitat Restoration/Enhancement team has planted giant bulrush in

vario us locations along the shoreline. “Giant bulrush is a bass magnet in the

spring,” Strickland says.

So what about the future? FWC stocked a total of one million advanced fingerling Florida bass in 2012, 2013, and 2015—twice as many as stocked in 2000 through 2003. If history repeats itself, those bass should start entering the fishery as trophy fish as early as 2018, and Strickland foresees a double-digit bass factory beginning in 2020. A proposed 16-inch maximum length limit (one over allowed), if approved, should stretch the boom for several years.

Best times to go: March-May for numbers; December-March for giants.

Nickajack Reservoir, Tennessee

Nickajack is a dendritic, 10,370- acre Tennessee River mainstem impoundment built in 1967. Although largemouth bass are most abund ant, healthy smallmouth and spott ed bass populations also exist. With Chattanooga near its upper end, the lake gets a lot of pressure. Even so, bass catch rate was almost one fish per angler hour, second highest in the state, in 2012. And the average largemouth caught weighed almost 3 pounds. Likely the 5 bass, 15-inch minimum length limit contributes to the abundance and quality of bass here.

Lake Chickamauga, immedia tely upstream of Nickajack, gained nationwide attention a couple years ago for big catches of huge largemouth bass. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) mana ging biologist Mike Jolley termed it a “perfect storm”—the coming together of effective stocking of Florida bass and production of the first- generation largemouth bass-Florida bass hybrids that supported the fishery, good habitat, and anglers disc overing umbrella rigs to mine the monsters in open water.

Jolley has applied the lessons learned in Chickamauga to Nicka jack, which has a good mixture of aquatic vegetation, brush, and stumpfields, as well as abundant shad. Although vegetation remains a wildcard, as TWRA has no control over its management, another perfect storm appears to be brewing. “Based on consistently high catch rates and large size structure in spring electrofishing assessments, the black bass population is in excell ent condition,”he says. “If the Florida bass stocking is successful, I predict Nickajack may rival Chickamauga within about eight years.”

But you needn’t wait. Next-door Chickamauga is still hot for trop hy bass. And the abundance and size structure of the Nickajack’s largemouth population are already impressive.

Best times to go: October, November, and February-May for numbers; March-May for big fish.

>> Increased coverage of hydrilla seems to have boosted catches of big bass at Lake Eufaula on the Chattahoochee River, AlabamaG eorgia, in recent years.

Lake Eufaula

(Walter F. George), Alabama/Georgia

This 45,000-acre Chattahoochee River impoundment has a history of cycling up and down, according to Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) fishery biologist Ken Weathers. Desirable coverage of hydrilla has benefited bass recruitment and somewhat stabilized these fluctuations; a 14-inch minimum length limit also appears to have helped. “The bass population promises fantastic fishing, but there are some ‘ifs,” cautions Weathers.

This 45,000-acre Chattahoochee River impoundment has a history of cycling up and down, according to Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) fishery biologist Ken Weathers. Desirable coverage of hydrilla has benefited bass recruitment and somewhat stabilized these fluctuations; a 14-inch minimum length limit also appears to have helped. “The bass population promises fantastic fishing, but there are some ‘ifs,” cautions Weathers.

The DCNR’s tournament reporting system recorded the lowest number of angler hours to catch a bass over 5 pounds in many years. Abundance of 5- to 6-pound bass means good numbers of 7- to 10-pound bass should be available next year. But they need food. As I write this (September 2015), anglers are commenting about “skinny” bass. Weathers’ team just completed their annual summer shad sample. Threadfin shad abundance is the lowest in four years, and the few shad collected were predominantly large ones over five inches.

But don’t write off Eufaula. Large threadfins are prime food for the abundant 5- to 7-pound bass, and Weathers is cautiously optimistic about good numbers of giant bass in 2016 and 2017. A good shad spawn next spring would mean fast growth for the abundant young bass spawned in 2014 and 2015, and that translates into a lot of quality-size largemouth for anglers to catch in upcoming years. Moreover, hydrilla provides good habitat for other forage, like bluegill and crayfish. So even with shad down, forage is available for bass.

Best times to go: Mid-March to mid-April and October to early November for numbers; late Janua ry to early March for quality fish.

Santee-Cooper Lakes (Lakes Marion and Moultrie), South Carolina

These two connected impoundments of the Santee and Cooper rivers provide about 150,000 acres of habitat-rich water. This dual impoundment was the place to go in the mid 1990s. South Carolina Department of Natural Resources fishery biologist Scott Lamprecht provided some data that suggest the largemouth fishery may be bett er than ever in a couple of years.

Marion and Moultrie consistently have moderately abund ant largemouth bass that grow fast and demonstrate good population structure. In almost every year since 1998, electrofishing samples reveal more than 50 percent of stock-size bass (longer than 8 inches) were larger than 15 inches and more than 10 percent were over 20 inches. That’s a large proportion of big bass. Want more evidence? Winning tournament weights last spring were consistently 27 to 31 pounds. Five-bass limits in summer and fall competitions were 17 to 24 pounds. And here’s the inside scoop: Lamprecht’s data show Moultrie had a substantially better size structure than Marion in 2015.

Lamprecht attributes part of the large size structure there to the 14-inch, 5-bass limit, but habitat management also helps. “Vege tation has been dynamic, and it’s been a constant battle to maintain native aquatic vegetation while cont rolling nuisance exotics,” he says. “Right now, everyone is dedicated to a good and stable amount of vege tation.” Add to this winning comb ination that the populations have a high frequency of Florida genes.

>Bass by

the numbers:

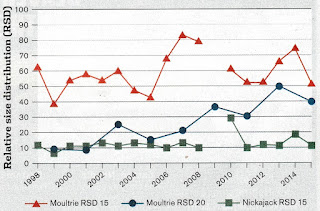

An effective way to monitor the size structure of a bass population is a simple statistic called relative size distribution (RSD). Input data are numb ers of largemouth bass sampled by electrofishing. This index is the number of largemouth bass greater than a specified length divided by the number of bass over 8 inches. The index is multiplied by 100 to eliminate decimals:

RSD X=(number of bass greater than length X)J(number of bass greater than 8 inches) X 100. RSD can be calculated for any length. In the following graph, RSD data are for RSD 15 (RSD for bass larger than 15 inches) and RSD 20 (RSD for bass larger than 20 inches). Lake Moultrie has a high proportion of bass over 15 and 20 inches. Samples were not collected in 2009, but note the peak in RSD 20 2 to 3 years after the peak in RSD 15. Nickajack has a gene ral upward trend in RSD 15, indicating an increase in population size structure.

An effective way to monitor the size structure of a bass population is a simple statistic called relative size distribution (RSD). Input data are numb ers of largemouth bass sampled by electrofishing. This index is the number of largemouth bass greater than a specified length divided by the number of bass over 8 inches. The index is multiplied by 100 to eliminate decimals:

RSD X=(number of bass greater than length X)J(number of bass greater than 8 inches) X 100. RSD can be calculated for any length. In the following graph, RSD data are for RSD 15 (RSD for bass larger than 15 inches) and RSD 20 (RSD for bass larger than 20 inches). Lake Moultrie has a high proportion of bass over 15 and 20 inches. Samples were not collected in 2009, but note the peak in RSD 20 2 to 3 years after the peak in RSD 15. Nickajack has a gene ral upward trend in RSD 15, indicating an increase in population size structure.

So how can it get better? Favora ble water levels after a decade-long drought produced strong year- classes in 2013 and 2014. Lamprecht expects catch rates to continue to rise in 2016 and 2017, with Mother Nature dictating the direction after that. “I’ve seen a 45-pound 5-bass bag in the past, and I expect to see more in the next couple years,” he concludes.

Best times to go: April-June for numbers; February to April for size.

Clarks Hill

Lake, Georgia! South Carolina

This 71,000-acre Savannah River impoundment is genera lly known as a numbers lake, but it’s one to watch for quality-size large- mouths in the next 2 to 3 years. Georgia Wildlife Resources Division fishery biologist Ed Bettross describes a rather circuitous path that may lead to improved fishing.

This 71,000-acre Savannah River impoundment is genera lly known as a numbers lake, but it’s one to watch for quality-size large- mouths in the next 2 to 3 years. Georgia Wildlife Resources Division fishery biologist Ed Bettross describes a rather circuitous path that may lead to improved fishing.

Striped bass are an import ant fishery in Clarks Hill. Aeration of inflowing Savannah River water has improved the summer habitat for blueback herring and striped bass, both of which need well-oxygenated, cool water in summer. Large stripers eat large gizzard shad. Improved water quality keeps big stripers abundant and feeding all summer. The stripers crop the big shad which, in turn, improves spawning and production of young shad. Thus by managing striped bass, Bettross is producing abundant shad forage for black bass. Clarks Hill is one of many southeastern reservoirs with strong largemouth bass recruitment but insufficient harv est of small bass by bass anglers addicted to catch and release, so abundant fora ge is needed to keep the bass growing. Increased angler harvest of bass under 15 inches bass would help.

With improved water quality, recent reserv oir filling after years of drought, and desirable amounts of hydrilla, Clarks Hill is poised to produce good numbers of 15- to 20-inch bass. Sampling in 2015 indicates relatively low numbers of bass over 16 inches, but high numbers of 12- to 16-inch bass. If water remains available and shad remain abundant, Bettross forecasts good numbers of bass over 18 inches in a couple years.

Best times to go: January, May, and September for numbers; March, May, and September for big fish. •

*Dr Hal Schramm, Starkville, Mississippi, is an avid angler, fishery biologist, and freelance writer. He frequently contributes to In-Fisherman publications on scie nce topics.

BEST LARGEMOUTH BASS WATERS ON THE HORIZON

4/

5

Oleh

Zzzz